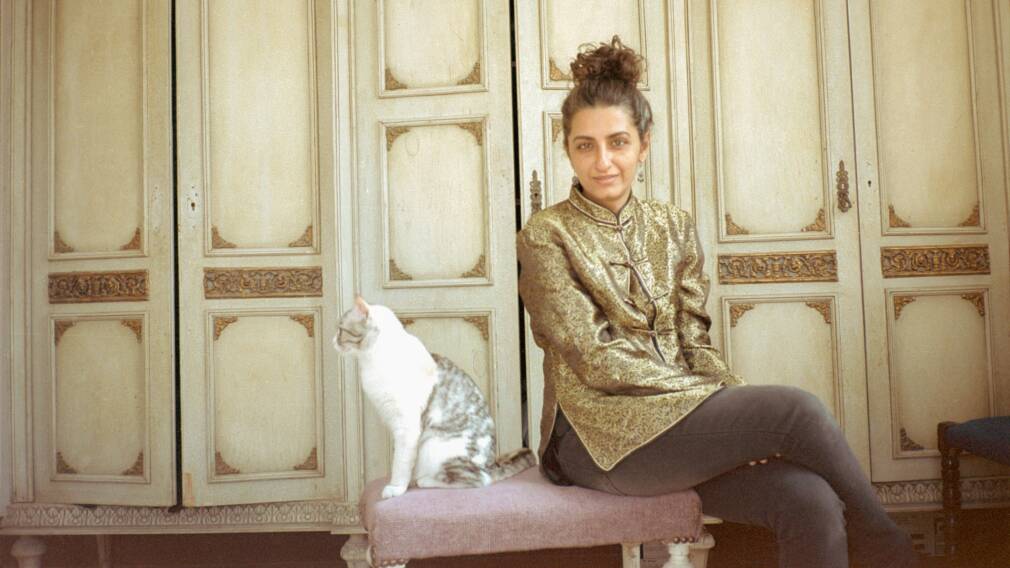

Nancy Mounir’s studio is where music comes alive in Cairo. Floating over rooftops in the heart of the city in unusual tranquillity for this part of town, its high ceiling walls adorned with violins, guitars and other string instruments that look foreign to a western eye. Mounir sits in between two pianos and her cat TamTamà, custodian of the studio. “Don’t pet her”, she warns with a smile as she turns towards her computer screen’s labyrinth of audio files. Mounir is an Alexandria born, Cairo based violinist, producer and composer. She lives amongst a plethora of instruments and plays them all. Her musical practice traverses genres from metal to classical; she composes and arranges scores and theatre plays, with her latest music production featured on Netflix’s short film ‘National Day of Mourning in Mexico’, directed by Khairy Beshara. In her studio, a carefully curated escape from Cairo’s overwhelming soundscape, she travels around the globe in discovery of alternative music scales and century old wisdom.

Mounir has spent six years researching Egyptian singers from the 1920s, tracing their musical lives and learning about tuning systems outside of the dominant scales in the Arabic mainstream. She composed Nozhet El Nofous (نزهة النفوس – Promenade of the Souls), her debut album which takes listeners on a journey through near forgotten worlds, guided by recordings of Abdel-Hay’s ‘Khafif Khafif’, El-Banna’s ‘Matkhafsh Alayya’, El-Mahdeya’s ‘Baad El Esha’, Sabri’s ‘Wallah Testahel Ya Albi’ and Serry’s ‘Ana Bas Saktalak’. Nozhet El Nofous revives the glorious years of eccentric Egyptian singers at the turn of the 20th century in an exploration of musical practice before the Umm Kulthum era. “I first started researching their music, because I deeply connected with what these artists were singing about”, says Mounir. “I believe them.” The icons she brings to life in her album make up the ancestral canon of musical rebels, tracing their passions, desires and afterlives in contemporary Egyptian society. Their education did not take place in schools, but with mentors whose knowledge was usually cultivated through reciting the Qur’an. The microtonal scales they worked with, called maqamat, are a mainly melodic system of tonal-spatial, rather than rhythmic, organisation. They are not based on a twelve-tone equal-tempered musical tuning system, as is the case in modern Western music. Instead, they include a perfect fifth or a perfect fourth (or both) and all octaves are perfect.

The Congress of Arab music

Microtonal unpredictability invites an existence beyond categories and genres. Studying this artistic tradition used to be a lengthy and deeply personalised process, mostly taught orally and through listening rather than through exact notation. “Microtones are used in rituals all over the world”, explains Mounir. “I believe that we were born to sing in microtones. Every ethnicity develops them in their own logic and through different trajectories.” She describes discovering microtonal scales as “if somebody entered my head and put their finger in places that haven’t been touched before”. It used to be common for musicians in different parts of Egypt to adopt their own unique tuning systems for their instruments. This practice was abandoned in 1932, after the Congress of Arab music was held in Cairo. In an effort to make Arab music more palatable to mainstream and western ears, and to simplify the difficult process of learning microtonal tuning, it aimed to document and standardise Arab music. In the newly adopted western-style notation system, microtones were rounded into their nearest quarter tone. As a result, a rich tapestry of microtonality was erased from Egyptian music, effectively putting limits on what was creatively possible.

Archiving those who were not invited

The artists that feature on Mounir’s album were not invited to this Congress, due to their self-expression and artistic choices that did not fit into the clean, nationalistic rhetoric being pushed at the time. The aftermath of this decision echoes through time as contemporary art worlds continue to debate the hierarchies of so-called high and low art. Pushed to the margins of the respectable performance industry, the artistry and impact of Mounir’s research subjects slowly faded from public consciousness. For her album, she recovered archival materials and recordings of several singers and composed her own music to reconstruct a non-existent memory. Nozhet El Nofous is a musical dialogue between Mounir’s own arrangements and who she calls “the ghosts”, exploring their legacies a century onwards. The project culminated in a performance at the very place where the Congress was held, the Institute of Arab Music, thus reviving these singers’ voices where they were once excluded and erased.

Mounira El Mahdeya

Known as “Sultana of Tarab“, Mounira El Mahdeya (1885-1965) was considered to be the leading Egyptian singer in the early decades of the 20th century. She began her career in local clubs in the entertainment district of Azbakeya, Cairo, where she sang Tarab, a style of traditional music that can loosely be translated to “ecstasy” or “joy”, describing the state of the audience when listening to the emotionally charged lyrics and microtonal intervals accompanied by drums, qanun, oud and the flute. In 1906, she recorded her first single under the name Sett Monirah (Lady Monirah), after which she soon rose to fame with her Arabic musical repertoire and as the inventor of Arabic opera. The explicit lyrics of some of her songs, which fall under the genre of taqtuqa, popular songs with romantic themes, still cause controversy to this day. In Baad El Esha, track four on Mounir’s album, she sings to her lover “I’ll expect you on Tuesday/ Tuesday, late in the evening/ You’ll find things all ready/ Electricity in my hands/ And I’ll sit with you at your pleasure/ There’ll be nobody there but us/ and no cause to be shy”.

The Sultana was the first Egyptian Muslim woman to stand on stage as an actress, defying the traditions of the time that forbade women to act on stage. She pioneered Egyptian revue theatre, a combination of singing, dancing, comedy, and drama that lasted all night long, and broke binaries by interpreting male roles and wearing men’s clothes to some of her concerts. “I dress as a man, because I feel like it”, she says nonchalantly in Mounir’s recordings. The years of El Mahdeya’s glory were characterised by perfumed and painted fluidities and openly artistic expressions of desire. “Listening to her speak in interviews, I learned that things do not have to be so complicated”, says Mounir. “Maybe we make them more complicated now.”

Hayat Sabri

Sayyid Darwich, the father of Egyptian popular music, discovered Hayat Sabri’s talent and helped her rise to fame as a singer and actress. He became her mentor and she his muse, a relationship that birthed famous songs like Wallah Testahel Ya Albi. Despite her intriguing voice and musical skill, Sabri was forgotten by the nation, unlike Darwich. “Initially, I didn’t want to have this song on the record, because everybody knows and remembers it as a Darwich song”, says Mounir. “But something in her voice, so full of pain, pushed to be part of the album.” Mounir’s performances feature a recording of Sabri conversing about the state of music in the 1950s. “Who feels like listening to the radio? Singers these days sound like cats yowling. All they sing about is love.” Her own lyrics, instead, tell of the power of education and the honour of Egyptian women: “A woman who can’t read or write/ will be taken advantage of/ A free woman can never be a disgrace/ A disgraced woman can never be free”.

Sabri’s singing career was cut short by two major heartbreaks. The first was Darwich’s death after which she slowly detached from life and completely halted her professional career. The second was the death of her son in the 1950s, which led her to choose to spend the rest of her life in the cemetery by her son’s grave, rumoured to be dead until a journalist discovered her. Mounir took several trips to her grave in Old Cairo. “I found grief and sadness and presence”, she remembers. “Something about time collapsed and I realised that it is not linear at all. Emotions travel through time and you can make a prayer in your present for something that happened a long time ago.”

Fatma Serry

Fatma Serry (1904-1975) was a singer, actress, and the first woman in Egypt to win a paternity case. Her first husband paid for her music lessons with Dawoud Hosni, one of Cairo’s most solicited composers who opened the doors of the night club world for her. In the 1920s, she was working as a successful singer when Hoda Shaarawi, the famous figurehead of Egypt’s women’s movement, invited her to perform at a party for the elite. In the audience sat Shaarawi’s son, Mohamed Shaarawi Bey, who was captivated by Serry. A stereotypical story of an aristocrat falling in love with a singer from a lower socio-economic class unfolded, followed by a love affair, a secret marriage, a child, and a patriarchal power dynamic that saw Serry pressured to give up her career to please her fiercely jealous husband. When his family refused to accept their relationship and child, Serry took them to court for almost six years, returning to the stage as a singer to afford the cost of legal counsel and persist in the pursuit of her rights. She eventually won a conviction in her favour and her daughter Layla was acknowledged to be the daughter of Mohamed Shaarawi. In Ana Bas Saktalak, Serry sings “A day will come when you beg me/ You’ll beg for us to reunite but I’ll refuse.”

In his groundbreaking book “Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring 20s”, Raphael Cormack recounts the cultural rivalries that were being played out in the music industry. While Mounira El Mahdeya and her fellow singers “revelled in eccentricity and unconventionality”, national hero Umm Kulthoum was “demure, reserved, and respectable”. Mounir agrees: “Umm Kulthoum played it safe. Mounira was wild, she didn’t care.” The album Nozhet El Nofous is titled after the Sultana’s prestigious sala, music hall, a place where artists, intellectuals and politicians gathered daily. Her famous venue inspired the popular slogan hawa’ al-hurriyya fi masrah Mounira El Mahdeya, the love of freedom is in the theatre of Mounira El Mahdeya. “The name carries the meaning of the journey”, smiles Mounir.